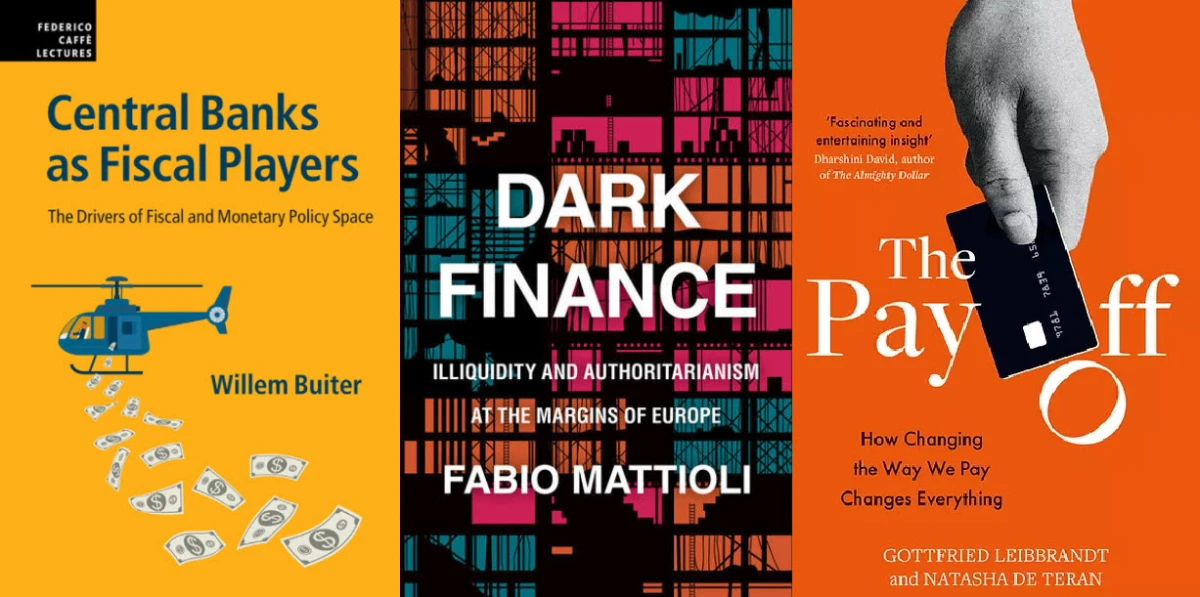

Last autumn I reviewed three books that highlighted different perspectives on money, finance, and central banking that deserve closer attention.

In the first book, Gottfried Leibbrandt and Natasha de Teran point out that the main reason to have money is to make payments – which means that when you start to change the payments system, you wind up changing just about everything connected to money. That ‘wallet’ on your cell phone is only the tip of the iceberg.

In the second book, Fabio Mattioli explains that when we talk about finance, we are primarily talking about forward looking contracts – and those contracts are only as good as their enforcement. By implication, a financialized economy looks very different when politicians start deciding which contracts will be honoured and which will not. Any debate about ‘rule of law’ goes to the heart of the financial economy.

In the third book, Willem Buiter reminds us that the central bank is a public asset owned by the national state. If national governments accounted for that asset in their balance sheets, they would uncover important revenue streams that could stimulate the economy and reduced burdens on taxpayers. The ‘helicopter money’ that policymakers talked about both during the global economic and financial crisis and at the start of the pandemic is not as strange or uncommon as you might think.

***

The Pay Off: How Changing the Way We Pay Changes Everything. By Gottfried Leibbrandt and Natasha de Teran. London: Elliott and Thompson, Ltd., 2021.

The classic definition of money revolves around three functions: unit of account, store of value, and medium of exchange. Two of these functions exist in the physical world in accounting ledgers and storage spaces (whether real or ‘virtual’, meaning electronic). The third is social insofar as a ‘medium of exchange’ presumes that someone, somewhere is willing to accept what you are offering how you are offering it. Most books about money focus on those physical dimensions, and so take the social aspect for granted. But money is not ‘money’ if you cannot exchange it with someone for something else. The most important part about money is payment.

The subtitle of Gottfried Leibbrandt and Natasha de Teran’s new book is not hyperbole. Changing the way we pay changes everything – or, at least, everything that has to do with money. The problem is that payment is so fundamental to the way we interact as individuals, firms, and governments, that is it almost impossible to grasp the full implications of that statement. Payment is not just about how Bitcoin is connected to mining or why some governments adopted the euro as a common currency while others refused. It is not even a question of how cash exists alongside credit cards, debit cards, signature cards, and payment cards. And it goes beyond the subtle distinction between having a pre-paid card and a checking account, or why people in some countries use checks while others do not.

So, it is time we start giving ‘payment’ the attention that it deserves because money means nothing without it. This is Leibbrandt and de Teran’s central message. They do not tell us where the world is headed but they do tell us where we should be focusing our concern. The three key elements are the possibility that people will have nothing to offer that others are willing to accept (liquidity), that one side or another will fail to complete the transaction (risk), and that somehow we might lose track of what people have and what obligations they are under (data). The ‘payment system’ is how societies manage these three elements.

The United States is the key to global liquidity because just about anyone is willing to accept U.S. dollars – even those who bear no love for Uncle Sam. This widespread acceptance of the dollar has practical implications. Someone has to manage the risks associated with the huge dollar-denominated transactions that connect many smaller transactions between less beloved currencies. When Dutch tourists splurge on an Indonesian ‘rice table’ while holidaying in Aruba, for example, you can be sure that U.S. dollars were used at some point in assembling the menu and probably also in paying for the dinner – not to mention making it possible for those tourists to get from the Netherlands to the Caribbean in the first place.

Banks are necessary to bring those small transactions together, to pool them with other transactions of varying sizes, and to make sure that all the final payments are made even if some of the individuals involved fail to deliver. Other firms may try to take up this role. If they are successful, governments will simply treat them as banks. American Express started as a delivery company.

The banks also need to keep track of who got what, when, how, and from whom. As Leibbrant and de Teran point out, this accounting is why writing systems developed in the first place. The technology for data management has been evolving ever since. As it does, payments necessarily evolve along with it. Leibbrandt and de Teran do a fantastic job introducing the many potential sources of disruption. They also highlight who wins and who loses from this rapid pace of transformation – particularly as the big tech companies get into the game. How we pay is changing and everything else is changing with it – even those things that look like they remain the same.

***

Dark Finance: Illiquidity and Authoritarianism at the Margins of Europe. By Fabio Mattioli. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020.

Finance is about contracting. Contracts are what financial markets trade. Those contracts set out the terms for payment and settlement – telling the parties involved who needs to deliver what, when, and to whom for their relationship to be complete. The binding legal aspect of this contractual relationship is important to create a sense of predictability. In that sense, it is also forward looking; while the contract is traded in the present, the relationship it describes extends into the future.

These three elements of contracting – the relationship, the predictability, and the forward-looking commitments – make financial markets very different from the market for other goods and services, where you can imagine a simultaneous transaction, like buying a pound of bacon. And to the extent to which those other markets also rely on forward-looking, predictable relationships, those contracting elements can be pulled out and recreated as financial transactions. Paying today for delivery of a pound of bacon tomorrow is a ‘forward’ contract; paying today for the opportunity to buy a pound of bacon tomorrow is an ‘option’. When academics talk about the ‘financialization’ of the economy, that reinforcement of the distinction between contractual, financial relationships and every other form of economic exchange is what they mean.

This is a long introduction to Fabio Mattioli’s brilliant ethnographic study of what happens in a society where political actors transform traditional economic exchanges into financial transactions, and then decide which contracts will be enforced while others will not. The range of political discretion is broad. Payments are delayed, new conditions are introduced, even the very nature of the exchange can be manipulated: You thought you would be paid in currency for the building you built; you learn later that compensation will come in fresh eggs. This puts a very different spin on the idea from Gottfried Leibbrandt and Natasha de Teran that changing the way we pay changes everything.

The problem, as Mattioli skilfully sets out, is that no single contract exists in a vacuum because the participants in any one relationship are bound up in many others at the same time. He focuses on the construction industry in Macedonia. That is an industry that obviously works over time, combining labour and materials to create important assets that are fixed in place. The firms involved have to contract with professionals to draft a project proposal, they have to secure use of the land for building, they have to hire the workforce and collect the materials, and they have to engage in a complex assembly process within which each element needs to be added at the right time for the project to come together successfully. A building without electricity or plumbing is a cave.

Construction cannot be done without numerous, overlapping contracts – each of which represents a point of leverage for interfering politicians. Everyone is aware of this problem, but no-one knows how to escape it. If you want to be in the construction business, that interference is the price you have to pay. This explains why it makes more sense for construction firms to get close to the regime than to try to work independently. Closeness not only improves the chances that their contracts will be enforced, but also that they will get an important building project in the first place.

Once the infringement of contracts begins, however, the results are immediately corrosive for the whole of society. Politicians manipulate contractors, contractors manipulate sub-contractors, and everyone manipulates workers. The authoritarianism that emerges is not only political; it permeates society. Mattioli sheds essential light on the dark side of finance. This is a book everyone interested in how development assistance and the ‘rule-of-law’ interact should read.

***

Central Banks as Fiscal Players: The Drivers of Monetary Policy Space. By Willem Buiter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

The global economic and financial crisis created a lot of confusion about the effectiveness of monetary policy and about the boundaries between monetary policy and fiscal policy. The effectiveness of monetary policy came into doubt as central banks approached the ‘zero lower bound’ for their policy interest rates. As a result, central banks started experimenting with new instruments like direct asset purchases. They also toyed with new settings on old instruments like charging negative rates (essentially a tax) on excess reserves held by commercial banks with the central bank. This is where the boundaries started to blur between monetary and fiscal policy.

Sometimes such confusion can be creative. Certainly, that is the case in the hands of former central banker and chief economist at Citigroup, Willem Buiter. Buiter starts by posing a simple question: who owns monetary policy authorities in the first place? If the central bank is the property of the national treasury, then it should appear as an asset on the balance sheet of the state. And when you look at the central bank as an asset, you uncover the whole range of profitable central banking activities that could be used to stimulate economic performance and alleviate the burdens on taxpayers. Importantly, this is not an argument for getting rid of the public debt by running high levels of inflation; it is also not an argument that the state faces no risk of insolvency. The point is that monetary policy and fiscal policy are more tightly intertwined than we are used to imagining.

That close interconnection unlocks a host of otherwise confusing buzzwords. Think about ‘helicopter money’. This is the idea that the central bank somehow prints money to be dropped onto households — an idea encouraged by the cover of the book. Buiter argues that there are many easier ways for central banks to distribute helicopter money than by air dop. The easiest involve the state. If the central bank purchases government debt and so holds down the cost of state borrowing, that is helicopter money because it frees up funds for the state to use elsewhere in stimulating economic activity. When the central bank hands over to the national treasury whatever profits it makes by exchanging zero-interest money for positive-interest government debt, that is helicopter money as well. And if the central bank holds onto that debt forever or reinvests the principal of its sovereign debt holdings on maturity, then it is as though the debt never existed.

Thinking of the central bank as a state asset changes the way we think about state solvency. Again, this point is not that the central bank should engage ‘monetization’ in some kind of irresponsible way. Rather it is that the state has an asset that can be realized to cover its borrowing requirements in the form of seigniorage revenue that does not necessarily jeopardize price stability. Buiter uses the consolidated inter-temporal budget constraint of the state to show just how significant that asset can be. When interest rates are very low, it could be as much as 10 percent of gross domestic product. He also shows how his own way of looking at the fiscal role of monetary authorities overlaps in part with modern monetary theory, particularly when monetary policy rates approach the effective lower bound.

Readers might disagree with Buiter’s accounting approach, and particularly with his view on central banks as fiscal players. If they do, they may discount just how important an asset a central bank can be in preventing sovereign default without provoking high levels of inflation. Buiter insists that this is a policy choice. You can see it in the design of the euro area, for example. Buiter’s point is not that Europe needs a fiscal union to pair with its monetary union. It is that Europeans already have a fiscal union via the European Central Bank, even if they do not realize it. The European challenge is to agree to share risks in ways that take advantage of the strength that fiscal union represents.

***

Follow @Ej_Europe These reviews were originally published in Survival. You can find the edited and published version here.