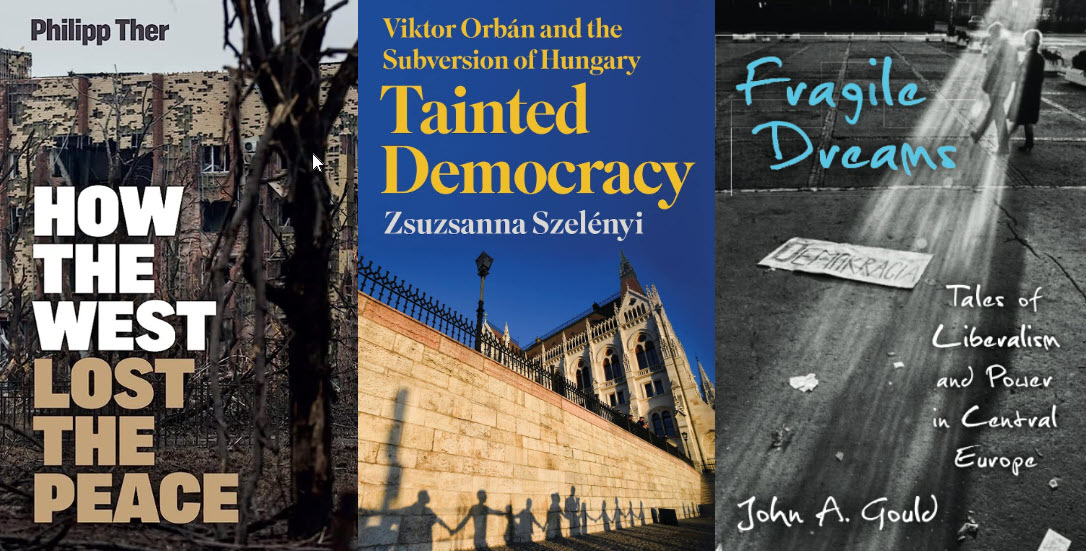

The usual story about the crisis of democracy centres on populists and other bad actors who spoiled the party for the all the rest. There is some truth to this account. But it only captures a small part of what is happening. To get a full picture, you need to look at the failure of democrats and democracy to deliver on what was promised. You also need to consider the perverse incentives that democratic institutions create. And you have to imagine that there are important groups of people – many of whom are poor and disadvantaged – who come out better under other systems of government (and for whom democratization has made things worse). These perspectives on the crisis of democracy do not deny the great promise that democratic institutions have to offer. But they do give pause to consider the many different challenges that democrats have to face if the project of giving power to the people is going to be a success. Three recent books by Philipp Ther, Zsuzsanna Szelényi, and John A. Gould explain why.

How the West Lost the Peace: The Great Transformation Since the Cold War. By Philipp Ther. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2023.

Sometimes capitalism and liberal democracy work well together, and sometimes they do not. As the Cold War came to an end, the West moved into a period of tension between capitalism and liberal democracy. While students and pundits debated ‘The End of History’, capitalist dynamics created ever widening inequalities that chipped away at the legitimacy of liberal democratic institutions. This was not the first time such tensions emerged. But it was the first time they did so at a moment when the political left lacked the ideas (or imagination) to redress the balance. Instead, the political left and right converged on a belief that there is no alternative to the capitalist free market economy. This admission of powerlessness was unpersuasive for those who could not accept the cost that the free market extracted and so the stage was set for political entrepreneurs – mostly from the right – to mobilize voters against liberal democratic institutions.

Philipp Ther uses this pattern of action and reaction as a framing device to explore different questions in a series of separate but linked essays. The first of these essays explains how this pattern connects to the ‘double movement’ described by Karl Polanyi in his classic study of the emergence of the global economy called The Great Transformation. Polanyi showed how each institutional reform necessary to create the liberal ‘free’ market resulted in both winners and losers. Polanyi also showed how the losers from those reforms quickly reacted to their fate by mobilizing politically to force the powers that be to offer either compensation or protection, but ideally both.

Those new compensatory institutions tend to disrupt the functioning of the free market, but they do not kill off the desire on the part of elites for further market liberalization. Instead, the cycle of reform and response repeats with ever widening oscillations in terms of conflict until either the market becomes embedded in society or society is broken by dis-embedded market institutions. Polanyi ends his book as both elites and society embrace the need to embed market institutions in broader social relations – the mixed economy and the welfare state. Using the same theoretical framing, Ther’s essays do not offer a clear ending but the trajectory he charts is less optimistic.

The essays work extremely well as provocations, and they deserve both wide distribution and sustained engagement. For this review, it is enough to illustrate the kinds of question Ther raises. Consider the notion of populism. Ther insists as a historian that the substance of populism merits more attention than the style of politics it represents. This turns out to be challenging. Although Ther labels Italy’s Five Star Movement as ‘left populist’, that group drew support from both sides of the political spectrum. It was only after the right of the party defected to the Lega that the Five Star Movement shifted decisively to the left. Now many of those Lega voters are shifting to further to the right to support the Brothers of Italy. What is the ‘substance’ that unites these three parties in the eyes of a large share of the Italian electorate? Ther’s argument about the United States raises similar questions. Ther traces Donald Trump’s success back to the 1996 campaign run by Patrick Buchanan. What he leaves out are even closer parallels to Ross Perot as a third-party candidate in 1992 and 1996. Should we regard Trump as the heir to a disenchanted right or as the successor to a mercurial business entrepreneur who wanted to take a turn at national politics?

The answers to these questions matter insofar as they reveal an even more disturbing possibility than the alternatives Polanyi offers: what if the people hurt by the dynamics of capitalism do not know the source of their own distress or the best remedies available? They could (and should) be forgiven for being ignorant. Their own politicians do not know either. The West may have lost the peace because liberal democracies chose to roll the dice with their political and policy choices and came up craps. Think North Stream II in Germany or the debt ceiling in the United States.

***

Tainted Democracy: Viktor Orbán and the Subversion of Hungary. By Zsuzsanna Szelényi. London: Hurst & Co., 2022.

Imagine two different conceptions of politics, one where social movements compete for control over institutions, and another where individuals struggle for power and legitimacy. Democracy could frame either notion; so, could just about any other system of governance. What is worth considering is whether the same constitutional arrangements would work equally well in both cases.

Zsuzsanna Szelényi offers a compellingly cautionary tale. In her account, Hungary started as a bold experiment in negotiated transition from communist authoritarianism to liberal democracy only to develop into something that is neither liberal nor democratic. The explanation is that Hungary’s constitutional arrangement was simply inappropriate to contain the personal ambitions that the fall of communism unleashed. Hence, the politics of that country quickly moved from a question of successful interest intermediation to a relentless quest by Viktor Orbán to ensure he has both power and legitimacy. If the country appears illiberal and undemocratic, that is only because Orbán can achieve his goals more easily in a nationalist and authoritarian context.

Szelényi’s personal political trajectory follows a different arc. She joined the Federation of Young Democrats, or Fidesz, to play an important part in a new social movement. Her goal was to move ‘beyond … inherited cultural conflict’ to push back against ‘communist hypocrisy’ and to ‘embrace the values of liberalism, the market economy, and the role of civil society in restricting the activity of the state’. When she entered parliament after Hungary’s first democratic elections in 1990, she respected that other parties gained representation and she focused on how to ensure that she and her colleagues positioned themselves to achieve as much as possible of their agenda.

As Szelényi tells the story, Orbán’s goals were more personal than ideological. He wanted to impose his own imprint on Fidesz while consolidating his hold on the party’s leadership and finances. Scandals emerged after Orbán enlisted support from his former schoolmate Lajos Simicska to sell the building given to Fidesz as a headquarters by the state and invest the proceeds in his own private companies. As Szelényi explains, Orbán had little interest in politics as a game of intellectual give and take. What Orbán wanted was control and autonomy. To do that he needed money which he trusted Simicska to manage. Szelényi and her allies rejected that arrangement and so left the party.

What follows is a complicated and yet fascinating story about how Orbán and Simicska built parallel, interlocking empires, both political and economic. It is also a story about how they legitimated these activities. Orbán shifts to the right to abandon liberalism in favour of a more conservative, communitarian ideology that can more easily justify his authoritarian inclinations by vilifying the former communists and pitching himself as the defender of Hungarian identity. Meanwhile, Simicska retreats from the public eye to manage a complex network of media, construction, real estate, and holding companies to promote Orbán’s vision of Hungarian society, benefit from local government contracts, build up real assets, and diversify holdings across the economy.

Of course, Orbán and Simicska were not alone in their ambitions. Szelényi’s account is replete with names of others who played key roles in regaining power and then eliminating checks and balances. She ably explains what flaws existed in the constitutional arrangement and how Orbán and Simicska exploited them. She also explains how, once they are safe from outside threats, Orbán and Simicska turned on one another. Orbán used his control over the state to defeat Simicska and replace him with Lőrinc Mészáros, who is less threatening to Orbán and whose business empire is now greater than anything Simicska had. Szelényi compares this to the Game of Thrones. The question she leaves us with is whether any constitutional arrangement can contain that sort of dynamic.

***

Fragile Dreams: Tales of Liberalism and Power in Central Europe. By John A. Gould. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021.

The key to understanding popular support for authoritarian regimes lies in the relationship between legitimacy and force. Authoritarian regimes use force to consolidate their hold over society. But no authoritarian regime could use force to achieve every policy goal. Therefore, even authoritarian regimes rely on popular perceptions of legitimacy to ensure that people comply with state policy without the need for active enforcement; states can only use force when doing so does not undermine their legitimacy. By implication, people support authoritarian regimes because they believe in some legitimating narrative about why those regimes exist, and because they also believe narratives about what makes the behaviour of those regimes – and particularly their resort to violence – legitimate. Once you learn those narratives, you will understand any popular support.

John A. Gould does a brilliant job using this relationship between legitimacy and force to unlock the complex politics that surrounded the dual political and economic transition from communism to capitalist liberal democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. In doing so, he sheds important light on why that transition never completely succeeded. He also explains why what progress has been made is constantly at risk of reverse. The key, Gould argues, lies in popular perceptions. For many people in the region, the introduction of liberal capitalist democracy did not constitute ‘progress’ despite the insistence of Western technocratic elites to the contrary. Opponents of liberal democracy are quick to exploit that perception with narratives about who is to blame and better alternatives.

Of course, the transition from liberal capitalism to communism was never that complete either, particularly in Central Europe. Gould uses the start of the book to explain how communist elites justified their takeover of society and the incredible use of force required to expropriate private property in the common interest. For anyone born after the mid-1970s, these chapters are an essential reminder of how liberal capitalism failed in much of Europe during the interwar period and why so many were eager to embrace an alternative. It is also a useful corrective to Manichean interpretations of Cold War social history. For many in Central Europe, life under communism was not all bad. Finally, Gould is careful to explain how even those who succeeded under communism came to recognize both its limitations and its excesses. In the end, too many stopped believing in the narrative and communist regimes consumed their own legitimacy through violence.

What Gould highlights is that liberal capitalist democracy also rests on a legitimating narrative about how the state should make room for individual choice and how individual choice should shape both politics and economics. Because that legitimating narrative centres on the protection of private property, moreover, capitalism relies heavily on the use of violence to protect private property rights. Unfortunately, that balance between individual freedom and state protection of private property is hard to strike because it touches on who wins, who loses, and why. Even worse, individuals tend to choose politically to work in exclusive groups when doing so will get them a larger slice of the pie. Liberalism and nationalism tend to reinforce one-another in that respect.

Gould explains how this liberal emphasis on choice fuels not just nationalism, but sexism, racism, and other forms of discrimination. Would-be autocrats create nationalist narratives about groups disadvantaged by an inequitable transition – unskilled workers, rural communities, older demographics – to justify the use of state violence against women, foreigners, and other minorities. Alas, the European Union has played an ambiguous role in this process. Worse, outside efforts to support more liberal narratives tend to backfire when would-be autocrats denounce them as illegitimate or use them to justify further violence. The picture Gould paints is sober, but the understanding he offers is fundamental to more effective support for liberal democracy.

***

Follow @Ej_EuropeThese reviews were originally published in Survival. You can find the edited version here.