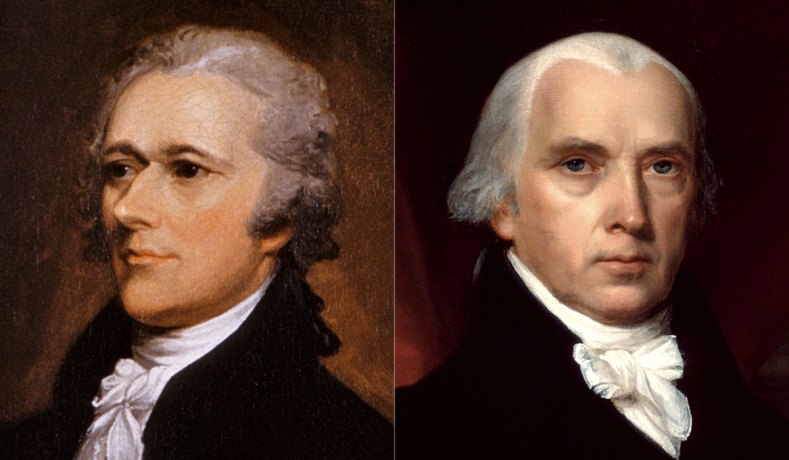

Has Europe has arrived at its Hamiltonian moment? That may not be the right question. Assuming these kinds of comparisons make sense, Europeans might want to focus more on Madison – and particularly his Federalist 10. Madison leads off the essay arguing: ‘AMONG the numerous advantages promised by a well-constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction.’ Translated out of 18th Century political jargon, Madison insists on the virtues of political pluralism as opposed to the vices associated with fixed political interests and coalitions; he also makes the case for a constitutional arrangement that balances the distinctiveness of individual states with the need for harmony across the union. That insight demands attention as Europe seems ever more deeply divided over how to respond to the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

European monetary integration has always had to balance between diversity and union; too often, though the people thinking about creating a common currency considered that balance in narrow, economic terms. Starting in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the principal concern among economists was that Europe is too diverse to support a monetary union through the mechanics of economic adjustment. The main focus was on the theoretical principles underpinning an optimum currency area – and the general conclusion is that Europe does not live up to the ideal. The euro would never work economically, as a result.

That conclusion turned out to be irrelevant because Europe’s leaders built the single currency anyway. So, the question became whether that new construct was going to be stable. So far as stability is concerned, it turns out that diversity has its advantages. In a book published in 2002, I made the point that every national government sees something distinctive in the euro, and that each had to make different and painful adjustments to join. When you add that diversity of interests and adjustments to the usual complexity associated with leaving a monetary union, there is every reason to believe that the single currency will hold together – because it will be much harder to dismantle that it ever was to create (and that was hard enough to warrant the phrase ‘unprecedented’).

The last crisis seemed to validate that argument. No matter what kind of pressure came to bear on countries like Cyprus or Greece, the governments of those countries preferred staying in the euro to the alternative. There was, however, an important caveat to my interpretation of the politics of economic and monetary union:

the greatest threat to EMU is not that one country or another might be disadvantaged or might even attempt to secede. Rather it is that EMU will become the focus for conflict between cleavages which cute across the monetary union, be it north and south or labor and capital or some other set of opposing coalitions. Whether the basis for such conflict is real or imagined may be less important than the symbolism of EMU as a crystallizing force. Such a conflict would bring order to the politics of EMU. However, it might also spell the collapse of EMU itself (p. 14).

The question is whether some structuring of the politics of Europe’s economic and monetary union was always on the cards. Certainly, that was the concern that Martin Feldstein raised in his 1997 article about the potential for the euro to create conflicts that could break the European Union.

What are the reasons for such conflicts? In the beginning there would be important disagreements among the EMU member countries about the goals and methods of monetary policy. These would be exacerbated whenever the business cycle raised unemployment in a particular country or group of countries. These economic disagreements could contribute to a more general distrust among the European nations. As the political union developed, new conflicts would reflect incompatible expectations about the sharing of power and substantive disagreements over domestic and international policies.

In the 1990s, Feldstein’s argument struck me as sensationalist. Now I am more cautious. There are some jumps in the argument I was unprepared to accept at the time, that are easier to fill in with benefit of hindsight (and thanks to the German constitutional court).

Nevertheless, I still think diversity makes for a better union. Here it is worth going back to Madison’s Federalist 10. What Madison argued is that divisions are an inevitable part of politics – particularly when we are talking about the distribution of wealth, income, or property. Rich and poor, debtor and creditor, are inescapable divisions. And it is ‘the principal task of modern legislation’ to find some way to balance these competing interests.

The problem for Madison was that the principle of democracy ensures that these divisions find direct expression in the legislative process – meaning that the interested parties are both making the decisions about what is to be done and reaping the benefits or suffering the consequences. Such a system is always prone to abuse given that individuals are always tempted to regard personal interest as more important than the general interest. Alas, the alternative of making decisions without popular involvement – and the liberty that comes along with it – is worse than the original problem.

The trick, Madison argued, is to find some way to temper the natural inclinations of the most powerful actors to impose their will on the rest. Failing that, the prospects for any form of government are not good:

such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.

Part of the solution, according to Madison, is to resort to a republican form of government where interests can be balanced locally so that decisions made at the center can focus more clearly on the good of the whole. This is true particularly when the variety of interests channelled through any given representative is large. It is even more true when the overarching union is large.

Both these conditions exist in Europe. The member states governments represent a wide variety of interests domestically and the European Union represents a variety of member states. The challenge for Europeans is to make use of these natural advantages.

In doing so, Europeans are going to have to find some way to resist the politics of faction at the European level while at the same time adding more discretionary authority into their rule-based framework for macroeconomic governance. The economists who worried about optimum currency areas were not wrong to focus attention on the problem of macroeconomic adjustment within a monetary union. The bankruptcies and unemployment that are coming fast on the heels of this global pandemic will not solve themelseves automatically through the smooth functioning of the market.

The problem of macroeconomic adjustment requires a political solution. And that political solution has to be agreed at the European level and then sold back into national electorates. The point to underscore with reference to Madison’s Federalist 10 is that there is nothing new in that requirement. Reconciling competing interest is still ‘the principal task of modern legislation’ – just as it was in the 18th Century.

Europe’s leaders need to make it clear to Europe’s many different peoples that finding some form of reconciliation is the only way they can ensure diversity and solidarity at the same time. Both challenges — resisting the politics of faction and finding some way to exercise discretionary authority at the European level — have been apparent for more than two decades; now they are imperative. Whether or not Europe’s leaders opt for a Hamiltonian solution for fiscal federalism, Europeans need to embrace Madison’s insights on the dangers of lasting division.

Follow @Erik_Jones_SAIS

[…] Not Hamilton but Mad… on The EU Needs to Admit Mis… […]

LikeLike

[…] Not Hamilton but Madison: Diversity Makes for a Better Union – by Erik Jones […]

LikeLike