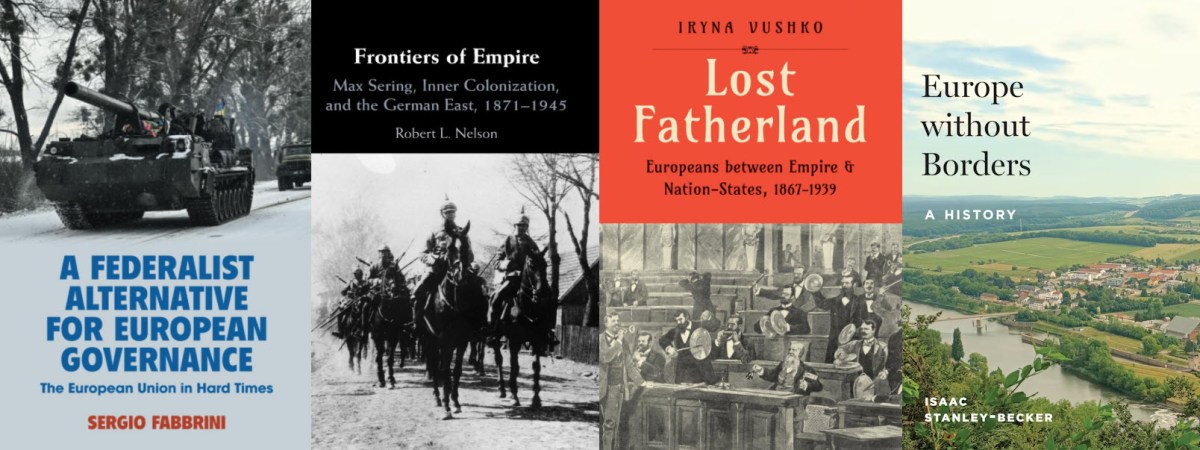

Four recent books – by Sergio Fabbrini, Robert L. Nelson, Iryna Vushko, and Isaac Stanley-Becker – challenge any presumptions about the uniqueness of recent European experience. They also force us to reflect on how the integration of Europe connects with the integration of individual countries (Fabbrini), how the experience of colonization has shaped the European continent (Nelson), how lessons from Europe’s imperial past continue to influence visions of its future (Vushko), and how the effort to promote freedom of movement has revealed a tension between nationalism and cosmopolitanism that runs across the European project (Stanley-Becker).

***

A Federalist Alternative for European Governance: The European Union in Hard Times. By Sergio Fabbrini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2025.

Contemporary theories of European integration emphasize power and process. They focus on intergovernmental bargaining among the member states, policy entrepreneurship within the European Commission, or coalition politics in the European Parliament. This focus sheds important light on how the European Union (EU) passes legislation and how it responds to crisis, but it tells us little about where the European project can and should be headed. Scholars (and policymakers) can imagine how to improve procedures on the back of such theorizing – for example, through greater use of qualified majority voting, more effective ring-fencing or sharing of competences, and more frequent engagement with popular representatives. They have greater difficulty imagining how to build political support around such reform measures, particularly when faced with countervailing narratives about the importance of preserving national sovereignty or cultural distinctiveness. And once member states or other affiliated governments begin to demand and receive exceptions, the resulting pattern of differentiated integration looks increasingly incoherent.

The solution, Sergio Fabbrini argues, is to stop pretending that the European project is unique or sui generis and to strengthen the theoretical toolkit by comparing the European Union to other systems of governance. The word ‘system’ is important. Fabbrini insists that on the need to redirect attention from the operation of specific institutions like the European Council, Commission, Parliament, or Court, to look at how these institutions work together both with each other and with the member states to meet the basic requirements for governance. From that systemic perspective, the EU is a compound polity like a confederation or federation that can be compared with other more-or-less similar arrangements. When doing so, the first question to consider is whether the goal of Europe is to bring together otherwise separate political entities as in Switzerland or the United States, or to decentralize political authority from an already strong centre as in Germany or Canada.

Fabbrini identifies the EU as a coming-together kind of federalism, which implies that some areas of sovereignty remain inextricably attached to its member states. It also means that those member states are more different from one-another in terms of population or other endowments than found in compound polities designed to decentralize authority. This combination of sovereignty and diversity places powerful constraints on the constitution of centralized political authority that do not exist in decentralizing federal arrangements. Those constraints explain why it is so difficult to reform specific institutions in the way existing theories of European integration recommend. They also point to a federalist alternative based on the constitutional features that work best in other coming-together arrangements. Fabbrini shows how we could re-order the EU as a three-tiered structure with a strong constitutional union at the centre, a community arrangement for those member states that do not want to work so closely together, and a confederacy offering even weaker association.

This federalist alternative gives a fresh and compelling perspective on how the EU can address current challenges, particularly as it faces the need to develop new competences and take on new member states in the face of a hostile geopolitical environment. Nevertheless, Fabbrini admits that finding the political will to embrace his recommendations extends beyond the scope of analysis (p. 210). That concession raises questions about whether the two types of federalism he offers can be taken as given. Coming together arrangements can evolve into centralized authority as in the Netherlands; centralized authority can take on the characteristics of coming-together arrangements as in Belgium. Spain and the United Kingdom have arguably moved in both directions, first centralizing and then decentralizing. Understanding the political dynamics that explain these transitions from one type to another also requires attention. The EU is coming together, but that cannot be taken for granted. Europe needs a compelling vision of where should be headed.

***

Frontiers of Empire: Max Sering, Inner Colonization, and the German East, 1871-1945. By Robert L. Nelson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024.

European nation states are anything but natural. The idea that one people, one culture, and one land would somehow come together took effort both to imagine and to put into practice. First someone had to identify the language that connected different and often mutually unintelligible dialects. Then they had to sort and shift different populations to bring like-minded or culturally affinitive groups together in the same place. And finally, they had to defend the fruits of that effort – both the people and the land – from other, competing projects. This process of nation-building involves both violence and institution building. And the more successful individual nations became, the more they threatened their neighbours through their attempts at consolidation.

The inner colonization of Europe started soon after the period of national integration in the mid-to-late 19th Century, as different nation-state building projects competed over the space between them. Moreover, everyone involved understood that national survival was at stake. Therefore, some of Europe’s greatest minds focused on how to make sure this inner colonization was successful – economically, legally, socially, and politically – even if they recognized that success would come at another people’s expense. What they failed to appreciate was the cost to their own societies.

Robert L. Nelson does a brilliant job using the life and work of Max Sering to reveal the clinical, scientific dimension European nation-state building. Sering was an agricultural economist who spent the better part of 1883 travelling across the United States and Canada to study different strategies for homesteading in the Great Plains region. What he focused on were the complex challenges associated with creating self-sustaining agricultural communities built around family-owned farms and relatively small urban spaces. Having grown up during the German occupation of Alsace-Lorraine after the Franco-Prussian War, Sering was familiar with the issues Germans faced with intra-European colonization. His goal was to draw lessons from the United States related to land speculation, inheritance law, and trade policy, for the German empire to use in settling Germans in Eastern Europe. Sering also gained insights on the differences in how Americans and Canadians treated their indigenous peoples; he preferred Canadian assimilation to the American alternative.

Sering quickly rose to prominence for his insights on inner colonization, agriculture, industry, and trade. His work gained attention and recognition on both sides of the Atlantic. Even Polish scholars whose people competed with the Germans for control over much of Eastern Europe sought Sering’s advice in trying to understand how to colonize the land successfully. And when Britain blockaded Germany and threatened the country with starvation during the First World War, Sering’s ambition to colonize Eastern Europe became a German imperative. What Sering did not anticipate is that his life’s work lay the predicate for the more extreme approach adopted by Nazi Germany with its violently racialized politics. He also did not recognize how the dispossession of people on the frontiers of Germany could undermine the support for the rule of law across the country. Sering opposed the Nazi’s, and yet he inadvertently empowered them through his ideas and his scholarship both in their authoritarianism and in their atrocities.

Nelson ends his history with the irony that Poland succeeded in colonizing that part of Eastern Europe that Sering most coveted for Germany. He also shows how interest in inner colonization extended into the 1970s with explicit reference to Israel and Turkey. His explicit goal is to normalize this European experience. All parts of the world have gone through similar moments, Nelson argues. Recognizing this comparison does not diminish the experience of Europe’s external colonies. Their suffering deserves recognition, as does Europe’s culpability.

***

Lost Fatherland: Europeans Between Empire & Nation-States, 1867-1939. By Iryna Vushko. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024.

Nationalism and extremism often seem like unstoppable, disintegrative forces. The collapse of Yugoslavia was a bloody, violent demonstration. Great Britain’s exit from the European Union twenty years later was very different in character and yet still powerfully disruptive. By contrast, cosmopolitan ideas of international or federal cooperation seem ephemeral and weak. Donald Trump’s administration can shake the foundations of the multilateral system that the United States created; right-wing nationalists in can jam up the functioning of the European Union. Meanwhile, globalist or federalist idealists struggle to offer a compelling or coherent alternative.

Then again, what shows up on the surface of debates like the ones that have dominated the papers in the past three decades may not be revealing of more powerful forces at work. Iryna Vushko underscores the possibility in her fascinating account of the lives and influence of key politicians at the twilight of the Habsburg empire around the turn of the 20th Century. Her argument is that the end of the World War in 1918 was less a rupture than many imagine. There are strong elements of continuity before and after that watershed than tell us much about the relative influence of nationalism, communism, fascism, and Nazism. Vushko’s goal is not to make comparisons between that period and the present. It is to stress that the influence of cosmopolitan experiences on the history of the 20th Century is greater than we might think.

Vushko focuses her attention on politicians who came from liminal communities in the Austro-Hungarian empire where nations and languages mixed freely, where Jewish people had the choice to assimilate or remain separate, and where the institutions of state and the rules, norms, and convention of society often operated separately. This environment was far from idyllic. The Austrians were capable of great brutality. The Poles and Ukrainians battled each other for territory and recognition. Different ideological groups – conservative, liberal, social Catholic, and Marxist – competed for political influence. Meanwhile irredentist forces sought to undermine the imperial state and to seize those territories that were owed to them by dint of historical providence. Her point is only that such an environment fostered important forms of pragmatism where language and nation did not have to coincide, politicians could work easily across different ethnic communities, ideology could make space for national autonomy – even among Soviet communists – territorial autonomy could be tempered by personal rights, and coalition building could operate freely.

Vushko claims this pragmatism played a crucial role in the development of Italian Christian Democracy and Italian Communism through the influence of key figures from Trentino and Trieste. She shows how it influenced the development of Czechoslovak nationalism, how it created a resistance to Austria’s Anschluβ by Germany, and how it divided families between Ukraine and Poland. These insight matter in ways that Vushko only hints at in the penultimate chapter of her book but that warrant strong repetition in the current environment. The extremes may capture attention in the popular conversation, but that does not mean they are all that is important.

Vushko also, implicitly, highlights the difference between those political entities that fall apart, like Austria-Hungary or the Habsburgs, and those that come together like Germany, Italy, or Poland. The coming-together entities are less pragmatic, more self-confident, and ultimately more aggressive. In that sense, Vushko’s book is a strong complement to Robert Nelson’s study of competitive colonization within Europe. It also offers a cautionary note on Sergio Fabbrini’s ambitions for a more self-confident, coming-together form of European integration. Such self-confidence may be necessary for Europe to succeed in a more competitive environment, but they also may unleash powerful integrative forces that few European federalists would willingly embrace.

***

Europe without Borders: A History. By Isaac Stanley-Becker. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2025.

The tensions between nationalism and cosmopolitanism cuts across the European project. The supranational, functionalist, and neofunctionalist forces are technocratic and therefore implicitly cosmopolitan. What matters is better policymaking, and whomever can deliver better or more effective policy should receive authority. The intergovernmental forces are nationalist and focus on the legitimacy of policymaking in a more representative, democratic sense. Such legitimation is unavailable to supranational institutions because they lack a coherent polity (or demos). The European Union (EU) is a political system, but it is not the Habsburg Empire reborn. And while the EU may be comparable with other ‘coming-together’ political communities (to borrow from Sergio Fabbrini, above), it remains dependent upon the ability of its member states to reach agreement.

Nowhere is this dependence more evident than in the free movement of peoples. The Schengen Area – which is the name given to the intergovernmental arrangement launched in the mid-1980s and since incorporated in the EU to facilitate borderless travel among those countries whose governments are willing and able to participate – is a powerful illustration. As Isaac Stanley-Becker shows in his compelling account of the history of Schengen, the right to borderless travel applies only to citizens of participating countries. Non-nationals can benefit from the lack of border controls on a temporary basis and at the cost of constant surveillance. If those non-nationals have residence, they can move freely but without relocation rights. If they lack formal papers, including temporary tourist status, they cannot move at all.

This dependence reflects a delicate balance between the economic advantages of borderless travel and the security concerns that any relaxation of border controls represents. Stanley-Becker shows how national negotiators achieved this balance, often with the assistance of European jurists. The language of the Schengen agreement characterizes freedom of movement as a complement to the completion of Europe’s internal market and not an expression of human rights. The relaxation of border controls makes it easier for Europeans to do business but also – at least potentially – exposes participating countries to greater risk of crime, terrorism, and the abuse of social welfare systems. The citizens of participating countries benefit from this freedom – and supranational officials hope this will help them identify with ‘Europe’ – but governments must earn the ability to participate through the collection and sharing of information on the movements of non-nationals, the harmonization of policing practices, and the acceptance of transnational arrangements associated with processing asylum cases, extradition requests, or hot pursuits. Such security matters make up more than half of the text of the implementing agreement.

Governments accepted these conditions only reluctantly, and with the reassurance that they could reintroduce border controls in case of need. Sharing information, amending asylum rules, and fostering cross-border cooperation in policing touch deeply on core state competences and hence national sovereignty. In turn, such arrangements exposed politicians in all countries to right-wing attacks that they put their own people at risk and threatened to water down national identity. Politicians also faced complaints from the left that the arrangement gave more freedom to goods, capital, and labour – as an economic activity – than to people as human beings. The fall of the Berlin Wall magnified such debates, as West European governments suddenly faced the liberalization of formerly communist, and hence ‘undesirable’ (p. 125) countries to the East, and so did the increase in migration from conflict-stricken former European colonies in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. Stanley-Becker does an excellent job puncturing the myths that Schengen is either a ‘laboratory of freedom’ or an expression of ‘fortress Europe’ (p. 272). Neither of these visions of Europe would have been possible without the other, and both are necessary for the Schengen Area to exist.

***

These reviews are four of five that were published in the June/July (2025) issue of Survival. You can read the whole set in its final edited (and hence also improved) form here.